Bridget Riley at the Hayward Gallery: A Deconstruction of Color

In the last half of the 19th century, Ewald Hering pioneered opponent color theory, which proposed that the human brain processes color by contrasting opposite tones, like red and green. Inspired by this controversial idea, Impressionists began dotting green bushes with bright red flowers, discovering that their juxtaposition increased each color’s vibrancy, breathing new life into their painting.

But for painter Bridget Riley, colors don’t just become more vibrant when juxtaposed – they become radically unstable and relative. As one stares at her work, the colors flicker and shimmer, occasionally becoming iridescent. To appreciate Riley is to understand that color is always mediated by its surroundings, and that categories like red and blue are perpetually unsteady.

London’s Southbank Centre is currently exhibiting a lifetime retrospective of Riley’s work in its Hayward Gallery. The exhibition spans 70 years of painting, ranging from her early copies of Georges Seurat, the pointillist cited as one of her primary influences, to her recent experiments with multi-colored dots. It includes many of her most celebrated works, like 1964’s “Blaze 1,” a mesmerizing black and white spiral certain to make any viewer’s head spin.

In 1967, Riley began experimenting with color in her abstract paintings. That same year, philosopher Jacques Derrida published Of Grammatology, famously declaring that there is no “transcendental signified.” Disrupting the dominant 20th century traditions of modernism and structuralism, he argued that there was no stable concept of reality to undergird our theories about the world. All we have are distorted perceptions, language games, and endless chains of signifiers.

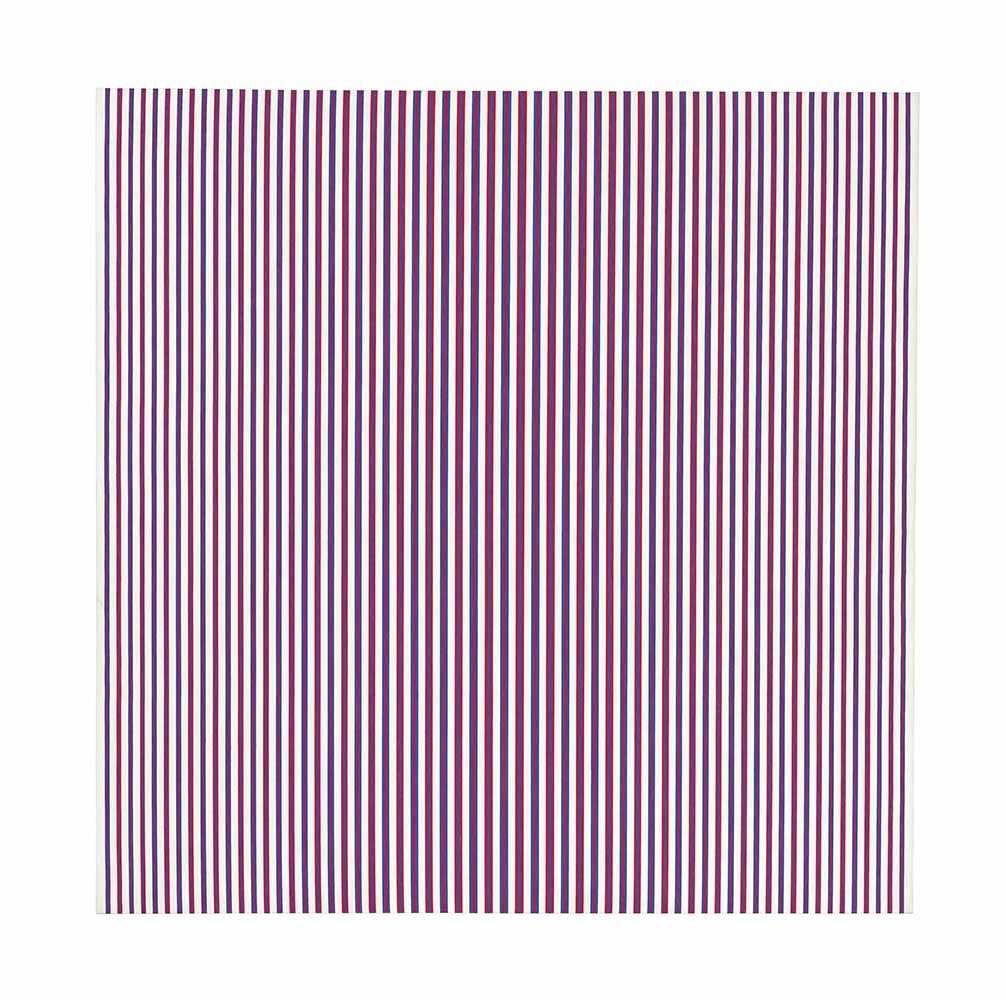

Riley’s 1967 “Chant 2” towers over the viewer, a 7.5 x 7.5 ft. square with red, blue, and white vertical stripes. In a kind of post-structural paradox that Derrida would enjoy, the longer the viewer studies the painting, the less it seems to make sense. What begin as three different stripes merge into varying shades of violet, along with what Riley describes as a “fugitive yellow” that traces across the canvas mysteriously, miraculously.

Because Riley’s paintings experiment with the viewer’s photoreceptors, in one sense, they abandon the notion of stability, much like Derrida’s philosophy. We can never see what “Chant 2” really looks like since the shapes and colors constantly shift, and at varying distances from the canvas it appears entirely unique. “Chant 2,” then, is not a single work of art but a multiplicity of different perspectives. The painting has no stable reality; the transcendental signified of art has vanished.

After about an hour of the exhibit, your humble writer experienced a searing headache, his brain exhausted from staring at color contrasts and floating black dots that refused to stay still – a headache not dissimilar from one experienced while first trying to read Of Grammatology. But before your eyes give up, Riley’s art is immersive and unforgettable, a joyfully creative experimentation into the possibilities of perception and reality.

Cultural Critic – Jack Wareham, Rhetoric Student at UC Berkeley

One Response

Very insightful! Truly captured the experience of viewing Reilly’s work!