A friend of mine who is a big Duchamp-ophile recommended that I read this book knowing that I myself have plenty of interest and opinions regarding the mastery of Marcel. This book was eye-opening (not retinally speaking) and a pleasure to read…

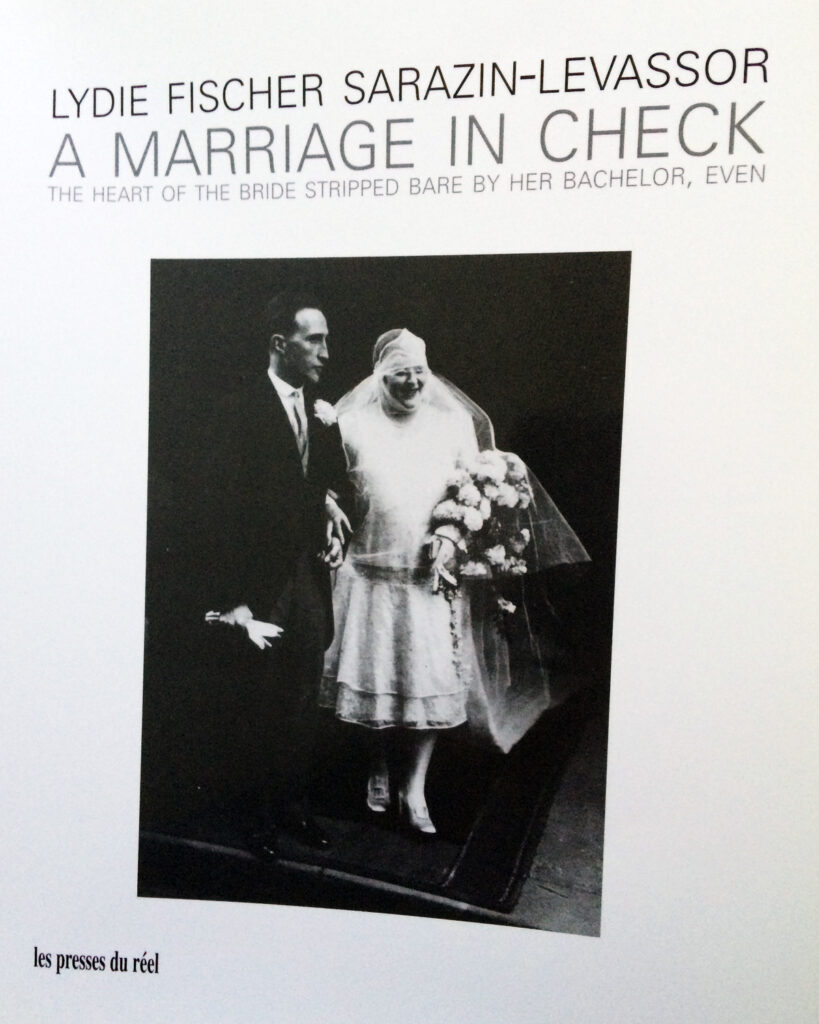

A Marriage In Check is a fascinating account by Marcel Duchamp’s first wife Lydie Fisher Sarazine-Levassor of their nine-month courtship and marriage. (L.F.S-L.)

From the first page we are privy to the awkward dynamic and suspicious circumstances of Lydie and Marcel’s initial encounter and subsequent engagement. She explains that her father, Henri Sarazine-Levassor, wanted a divorce from his wife of 25 years and that Mrs. Marthe Sarazine-Levassor would only acquiesce once their only child Lydie was married off. This unusual request may have come less out of concern for her daughter and more as a means of preventing the divorce. Lydie was a twenty-five year old recluse, overweight and by her own account not very attractive. For a while Marthe Sarazine-Levassor’s plan seemed to work as her daughter was unable to attract a suitable suitor. That was until Henri Sarazine-Levassor’s friends, the artist Francis Picabia and his then mistress Germaine Everling, decided to help. From this account Picabia and Germaine were instrumental in introducing Lydie to the charming, available and broke Marcel Duchamp. Marcel’s money was tied up with a large Brancusi purchase and he had become preoccupied with chess. Duchamp had publicly renounced art and proclaimed to Lydie that he did not work for a living but would live off his chess winnings or other laissez–faire endeavors. Lydie and Marcel received the slightest of dowries, one that proved too small for the both of them to live off. This strained their marriage from the outset and what money they did have was spread especially thin because Marcel needed his own space to work. They began to live separately and ultimately, Marcel asked for his freedom, telling Lydie that a divorce will not change anything and may help their relationship. Lydie wondered what happened; why did he marry her in the first place? Lydie began to suspect a conspiracy between her husband, her father and their mutual friends and was guilt-ridden that her marriage forced her mother to succumb to the father’s will. Although Lydie was never fully embraced by Duchamp’s artistic milieu she did hope to win Duchamp’s love and trust, thinking that over time she would be accepted by Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Katherine Dreier and the rest of Duchamp’s posse. But this arrangement seems to have been a Fait accompli and those close to Duchamp (except for Duchamp’s youngest sister, Yvonne) kept Lydie at arm’s length when not interrogating her tastes and morals. This is a compelling read that gives the reader insight into familiar personalities and avant-garde artists from an alternative and unique perspective. It is also a wonderful window into the chaos of post-World War I France and the changing class-consciousness that would become prime subject matter for the avant-garde during the twenties. Lydie Fischer Sarazine-Levassor’s observations and remembrances were written not as a salacious tell-all or as art history but rather for a Duchamp retrospective occurring at the Pompidou in Paris, 1977. I recommend this book to anyone who would like a better comprehension into the life and character of Marcel Duchamp the man, not the artist.